|

The following article was researched and written by Carl Miller for the Steubenville (Ohio) Herald-Star for its annual "Progress Edition."

Fine Brews Made in Steubenville. Fine Brews Made in Steubenville.

In many cultures, beer has been among man's daily essentials for

thousands of years. The earliest references to beer reveal that

Mesopotamiams regarded brewing as a noble profession over 6,000 years

ago. Egyptian writings pronounced to be about 5,000 years old also

mention beer. And although the Bible makes no reference to brewing, an

Assyrian clay tablet of 2,000 B.C. lists beer among the supplies taken

aboard Noah's Ark.

In more recent history, too, beer has played a role. According to a

journal kept by a passenger on the Mayflower, the Pilgrims' decision to

land at Plymouth Rock was made because "we could not now take time for

further search or consideration: our victuals being much spent, especially

our bier." And several figures in early American history dabbled in beer

making, among them George Washington, Samuel Adams, and Thomas

Jefferson.

It is not surprising, therefore, that beer has been ever-present

throughout the development of America. During much of the nineteenth

century, breweries flourished in virtually every American city or town.

And Steubenville was certainly no exception. Proximity to the Ohio River

meant easy access to large beer-consuming markets like Pittsburgh and

Wheeling. As a result, Steubenville was home to some of the earliest

breweries in the state.

In 1815, a man named Dunlop established Steubenville's first

commercial brewery on N. Third street near where the Hartje paper mill

then stood. By 1818, the brewery had been taken over by Charles F.

Leiblin, who conducted it for several years before brewing ceased

sometime during the mid-1800s.

Alexander Armstrong set up a brewery in 1819 on Water street near

Washington. Joseph Basler, a former brewer at Leiblin's operation, was in

possession of the Armstrong brewery by 1836. Sons Joseph Jr. and Max

Basler successfully ran the works for many years, brewing as much as

2,000 barrels (32 gallons per barrel) of beer annually by the 1870s. Alexander Armstrong set up a brewery in 1819 on Water street near

Washington. Joseph Basler, a former brewer at Leiblin's operation, was in

possession of the Armstrong brewery by 1836. Sons Joseph Jr. and Max

Basler successfully ran the works for many years, brewing as much as

2,000 barrels (32 gallons per barrel) of beer annually by the 1870s.

The products of these and other early Steubenville brewers was vastly

different from most of the beer consumed today. The German-originated

lager beer, which has dominated American beer tastes for more than a

century now, was not yet known to the city's pioneer beer makers. Instead,

English style ales, porters, and stouts were the norm.

However, the great flood of German immigration into America

throughout the mid-1800s affected a virtual beer revolution. The Germans

-- and their unperishable love of lager beer -- transformed brewing in

America into a burgeoning industry.

Although Steubenville did not boast particularly large numbers of

Germans during the nineteenth century, it was nevertheless a lager beer

brewery which ultimately prospered far more than any other brewery in

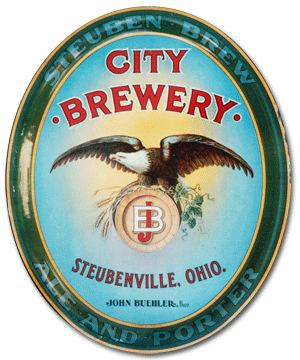

Steubenville. In 1860, German immigrant John C. Butte erected a small

lager beer brewery at the base of the Adams street hill. Known simply as

the City Brewery, Butte's operation provided beer to Steubenville residents

for nearly the next sixty years.

In order to achieve the cold temperatures necessary for aging lager

beer, Butte excavated cellars 100 feet deep into the solid rock hillside

adjacent to his brewery. The beer was kept cold with large blocks of ice

harvested during winter, while the cool underground temperatures helped

preserve the ice well into the warm season. In their day, Butte's aging

cellars were called "the finest and most complete" in Ohio.

Although that characterization may have been a little exaggerated, the

City Brewery was nonetheless enjoying a healthy trade by 1872. Its beer

was consumed not just locally, but was also shipped in both directions on

the Ohio River. Six men were employed at the brewery, and production

amounted to about 100 barrels of beer per month. Plans for expansion

were under way, and it was predicted that the brewery's output would

climb immediately to 150 barrels per month as soon as the additions were

completed.

Butte remained in the City Brewery for more than 25 years (although

briefly relinquishing ownership to business partner Bernard "Benj" Miller)

before selling the works in 1886 and retiring.

The new proprietor, Charles L. Rall, was a native of Pittsburgh who

had spent his early manhood learning the brewing trade in Milwaukee. Rall

operated the brewery under the partnership of Rall and Klein until 1887,

when he bought his partner's share in the business for $2,000.

In 1895, at the young age of 38, Charles L. Rall unexpectedly passed

away. The coroner ruled that death was caused by "softening of the brain,"

a typical diagnosis of the day. Rall's widow sold the City Brewery the

following year to John Buehler, a recent arrival from Pennsylvania. Born

in Germany, Buehler had studied the art of brewing in the province of

Wurttemburg before emigrating to America in 1887. After graduating

from the United States Brewing Academy in New York City, and working

in breweries in Connecticut and Pennsylvania, Buehler came to Ohio to

take over operation of Steubenville's lone brewery.

John Buehler immediately began a major overhaul of the City

Brewery. Artificial refrigeration -- perhaps the single most important

development in the brewing industry during the nineteenth century -- was

added to the plant in 1898, thus rendering the old underground aging

cellars obsolete. And in 1901, an entirely new brewhouse and stockhouse

was erected, complete with its own electric power plant.

Indeed, those brewers who entered the new century without modern,

efficient operations were ill-equipped to contend with what would prove to

be competitive times ahead. Names like Budweiser, Schlitz and Pabst --

with aggressive distribution and promotion behind them -- were quickly

becoming a serious threat to small regional brewers everywhere.

In Steubenville, one observer estimated that as many as fifteen outside

brewing companies were represented locally by independent agents or

brewery-owned distribution depots. Saloons, where the vast majority of

beer was sold in the early days, were aggressively targeted by outside

brewers. A popular sales tactic was to push bottled beer rather than kegs,

so that saloonkeepers need not add extra tapping equipment in order to sell

a new brand side-by-side with the local brands.

Many regional brewers sought to protect their local trade by

purchasing large numbers of saloon properties, thereby locking out

competition. But John Buehler refused to engage in this rather expensive

and troublesome strategy, maintaining that he was in the beer-making

business, not the "retail thirst" business.

However, Buehler recognized that ever-increasing competition would

require special measures. A new bottling plant was erected adjacent to the

brewery and, in 1907, Buehler introduced a bottled beer called Steuben

Brew for the expressed purpose of competing with outside brands. The

new Steuben Brew became the feature product among the brewery's other

brands -- City Brew, Pale America, and Select.

Growing competition was not the only menace to brewers during the

early part of century. Nor was it the most threatening to the industry's

well-being. A strong Prohibitionist movement had been under way in

America since the mid-1800s. Anti-liquor groups like the Women's

Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League had begun to

make inroads in legislative circles by the turn-of-the-century.

In 1908, legislation was enacted in Ohio which gave every county in

the state power to render saloons illegal by a public vote. The voters of

Jefferson County elected by a wide margin to abolish their 141 saloons,

about 80 of which were inside Steubenville proper. The manufacture of

beer was still legal under the new law, allowing the City Brewery to

continue selling beer to saloons in wet counties, as well as to local

households. But the bulk of the brewery's trade had been the area saloons,

and survival under the new conditions was difficult.

In the absence of legal saloons, "speakeasies" were soon rampant

throughout the county. Local authorities, in their battle to gain control of

the situation, targeted John Buehler as a primary source of the trouble. It

was charged that a great majority of beer consumed in the illicit drinking

spots came from the City Brewery. And Buehler soon found himself facing

a handful of criminal convictions for illegal sales of beer.

Buehler, of course, vehemently denied any wrong doing. But, in the

end, he was forced to close the City Brewery in order to avoid further

prosecution. Early in 1910, production stopped and it was announced that

the brewery would remain idle as long as the anti-saloon law was in

effect.

Illegal drinking establishment continued in abundance regardless of the

brewery's closing. Realizing that anti-saloon enforcement was failing

miserably, the citizens of Jefferson County voted to re-legalize saloons

effective January 2, 1912. By January 5th, plans had already been put in

place to reopen the City Brewery. The Steuben Brewing Company was thus

incorporated by John Buehler, his son Charles T. Buehler, and several

local businessmen. Also involved in the venture was Steubenville Mayor

Thomas W. Porter (1908-1913), who ultimately served as the brewery's

vice-president. The production of Steuben Brew was resumed as before,

and the brewery eventually regained sound footing.

Be that as it may, the efforts of the Prohibitionist forces did not slow,

and it was only a short time before Ohio's brewers were again facing

disaster. In a 1918 referendum, the entire state of Ohio was voted

completely dry, to take effect the following year. And passage of the 18th

Amendment to the Constitution soon followed, thus enacting National

Prohibition.

By September of 1919, the Steuben Brewing Company had been

dissolved and the brewery was producing soft drinks and near beer (de-

alcoholized beer) as the Steuben Beverage Works. Countless brewers

sought survival with similar products, and the vast majority met with quick

failure.

In 1920, the Buehlers leased the old brewery to the Premier Malt

Products Company, an Illinois-based manufacturer of malt syrup. Charles

T. Buehler, who had spent several years working with his father in the

brewery, was hired as manager of the Premier operation.

However, the production of malt syrup was halted in 1924, and the

plant was closed. Charles T. Buehler, on a fast track within Premier's

management, moved to Peoria, Illinois, where Premier later merged with

the Pabst Brewing Company of Milwaukee. Interestingly, Charles T.

Buehler ultimately held a position as one of Pabst's highest-ranking

officials.

John Buehler, incidentally, also made the move to Peoria, where he

spent many of his remaining years in retirement. He died in 1934 while

vacationing in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Upon the repeal of National Prohibition in 1933, efforts were made to

re-open the old Steubenville brewery. The Fort Steuben Brewing Company

was organized by a group of local businessmen, among them the owners of

the Steubenville Pure Milk Company which had purchased the brewery

buildings several years earlier. The new brewing venture did not fully

materialize, however, and Steubenville was never again home to its own

brewery.

The entire brewery complex still stands today at the base of the Adams

street hill, occupied since 1960 by the Famous Supply Company. The well-

preserved buildings -- with arched windows and staid brickwork so

characteristic of early breweries -- serve as a quiet reminder of the day

when every town enjoyed its own hometown beer.

|