|

Reprinted from the Marion (Ohio) Star.

Marion Brewery Made 'Best Beer In The World.'

by Carl Miller

Given that nearly every city or town of any consequence supported a

brewery or two during the industry's turn-of-the-century heyday, it is not

surprising that Marion once held a position, modest though it may have

been, among the nation's great brewing cities.

Noted beer-manufacturing centers such as Philadelphia, New York,

Cincinnati, and Milwaukee each boasted dozens of thriving breweries

before National Prohibition (1920-1933). And how many in Marion? Well,

just one. But the people of Marion took pride in their lone brewery, and in

drinking a beer that was brewed right at home. Consequently, the brewery

enjoyed a fairly prosperous existence for nearly twenty-five years.

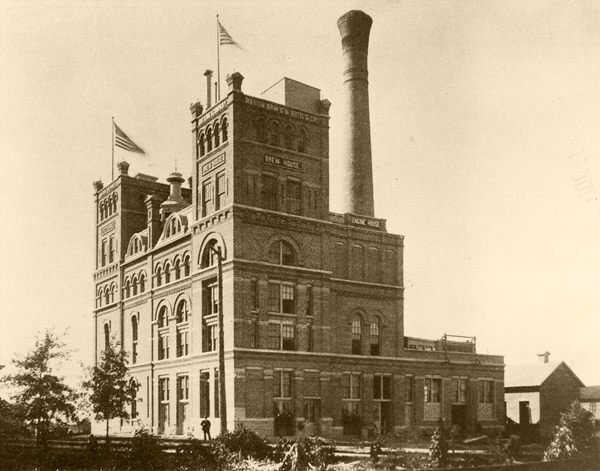

It all began in 1894 when a group of area businessmen founded The

Marion Brewing & Bottling Company. Mansfield business owner Frederick

Walter was said to have been the primary figure behind the venture and,

accordingly, he was elected the brewery's first president. By November of

the following year, construction of the monumental new brewery at 640

Bellefontaine avenue was complete and the first batch of brew was

begun.

However, brewing beer in the early days was not an overnight affair.

The old-time brewmaster, who typically learned his craft under strict

European training, had final say on all matters within the brewery,

including when the beer was ready for consumption. Charles Earnest,

brewmaster at the Marion brewery, was not about to release his inaugural

brew even one minute before its maturity, lest his reputation be tarnished

from the outset.

After nearly an entire winter's wait, the citizens of Marion were given

the first taste of their hometown beer in February of 1896. Called simply

"Marion Beer," about 100 kegs of the brew were released, two-thirds of

which were consumed by saloons within the city. The remainder was sent

to outlying areas.

Advertisements for the new Marion brew made the rather bold claim

that, "The Best Beer In The World Is Made In Marion. That Is The Verdict

Of All." Those wishing to put that claim to the test were initially forced to

do so exclusively at saloons. Bottling for household purposes, which was

often a secondary consideration for brewers, did not begin at the Marion

brewery until later in the year.

Before Prohibition, as much as 90 percent of all beer was packaged in

wooden kegs. Take-out beer often involved going to the local saloon with a

small tin pail, called a "growler," and having the saloonkeeper fill it,

usually at a cost of a nickel per growler.

Bottling was a troublesome task for early breweries, mainly due to the

menacing tax restrictions which mandated that all beer be kegged initially,

then bottled direct from the keg in a building separate from the brewery.

The early lack of an effective bottle enclosure, too, meant frequent leakage

and often resulted in spoiled beer.

Nonetheless, the Marion Brewing & Bottling Company, as suggested by

its name, saw a bright future in bottled beer. Among the Marion brands

which were available in bottles were Amber Ale, Cordial Brew and

Walhalla Export. The latter brand was named in honor of the legend of

Walhalla, a place in Scandinavian mythology where the souls of slain

warriors feasted on a never-ending supply of food and drink. A colorfully

titled brand name, after all, could only help to stimulate beer sales.

By about 1910, however, the Marion brewery had become best known

for a brand called Banquet Brew, which was promoted vigorously as the

brewery's feature product. Households were encouraged to place orders

for Banquet Brew by telephoning the brewery, from whence a case of the

bottled beer would be promptly delivered. This type of service reflected

the brewery's strong commitment to its local market.

Indeed, The Marion Brewing & Bottling Company was truly a local

entity. Nearly all of its directors, and most of its stockholders, were

prominent local business owners and men of fine repute within the

community. Clearly the most noted individual to be connected with the

brewery was Warren G. Harding, who held stock in the Marion brewery

for much of its existence. During his bid for the presidency, Harding once

commented, "I am not a prohibitionist and never pretended to be...I have

been owner of brewery stock for 25 years."

Among the directors of the brewery over the years were such local

business figures as Timothy Fahey, president of the Fahey Banking

Company; Godfrey Leffler, founder of the contracting firm of Leffler &

Brand; William E. Scofield, senior member of the law firm of Scofield,

Durfee & Scofield; and Oswald Wollenweber, president of the

Wollenweber Lumber Company.

Despite this pool of presumably keen business savvy, the Marion

brewery did not operate on a particularly large scale, even by the standards

of its day. The brewery's annual capacity was reportedly 25,000 barrels

(32 gallons per barrel), but its actual output seems never to have reached

that capacity. In 1897, the brewery sold approximately 7,000 barrels, an

amount equal to about one hour's output of any major brewer today. And a

whole decade later, production had only increased to about 8,000

barrels.

Perhaps one reason for the brewery's relatively limited production was

the constant threat posed by the prohibition movement. Beginning around

the turn of the century, the war which had been waged against the beer and

liquor industry for decades began to gain new strength. The fight was

particularly active in rural Ohio, where prohibition was favored by the

majority.

In 1908, the Rose Law was enacted, which allowed all Ohio counties to

prohibit the operation of saloons within their boundaries by a popular vote.

Marion County promptly voted to shut down all of its 49 saloons,

essentially wiping out the Marion brewery's primary market.

Surprisingly, the new law was accepted with a healthy degree of

optimism. Several of the city's saloons vowed to remain open, serving only

non-alcoholic beverages.

The brewery began plans to produce near beer, a de-alcoholized

version of real beer. A spokesman for the brewery was quoted as saying,

"With the manufacture of near beer, we expect to make more money than

we have through the manufacture of our present brew."

But performance of the non-alcoholic beer did not meet expectations,

and the brewery was soon seeking outside markets for its original brands.

As most of the surrounding counties also voted themselves "dry" under the

Rose Law, the brewery undoubtedly relied heavily on the Mansfield and

Columbus markets for its survival.

Despite the cries of the anti-saloon factions, abolishing the saloon, it

was discovered, did not solve "the liquor problem," and Marion County

returned to legalized drinking establishments in 1911.

However, the citizens of Marion County rarely ignored an opportunity

to show their support for the prohibition movement. In a 1915 referendum

for statewide prohibition, Marion County voted 4,726 to 3,588 in favor of

prohibiting the possession, sale, and manufacture of alcoholic beverages

inside Ohio.

Although that attempt failed throughout the rest of the state, a similar

vote in 1918 succeeded in effecting statewide prohibition, thus spelling ruin

for all of Ohio's breweries. A year later, the entire country followed suit

with adoption of the National Prohibition Amendment.

The Marion brewery, like breweries nationwide, faced a bleak future.

Many turned to the production of near beer, soft drinks, ice, and dairy

products. But the owners of the Marion brewery, not wishing to venture

the necessary capital to enter new fields, elected not to continue in business.

Consequently, the brewery, which had been valued at $135,000 and had

employed between fifteen and twenty-five men (depending on the season),

closed its doors for good.

The old brewery buildings, stripped of all of their brewing equipment,

were used for various purposes over the years. Automobiles were stored in

the brewhouse during the 1920's, and the bottling plant served as

warehousing for a biscuit company. By 1938, the brewery had been taken

over by the Betty Zane Corn Products Company, which processed popcorn

there until the 1970's. After sitting idle for a number of years, the

brewery's main building was demolished in 1980, leaving only a parking

lot in its place.

The saga of the Marion Brewing & Bottling Company is not unlike that

of hundreds of other small American breweries which prospered before

Prohibition. Little remains from the day when nearly every town of any

size took pride in supporting its own hometown beer.

In Marion, two small buildings at 636 Bellefontaine avenue are all that

remain of the once thriving brewery. Exhibiting few signs of their proud

heritage, the buildings serve as somewhat of a humble monument to an era

long forgotten.

|