[an error occurred while processing this directive]

Antique Beer Photos:

Dozens of prints available in a variety of sizes up to 40x50. |  |

|

|

Gottfried Krueger: Epitome of a German-American Brewer Gottfried Krueger: Epitome of a German-American Brewer

By Carl Miller

[Reprinted from "Decadence & Decay," Paul Robeson Galleries Program, Rutgers University, Newark, NJ, 2009.]

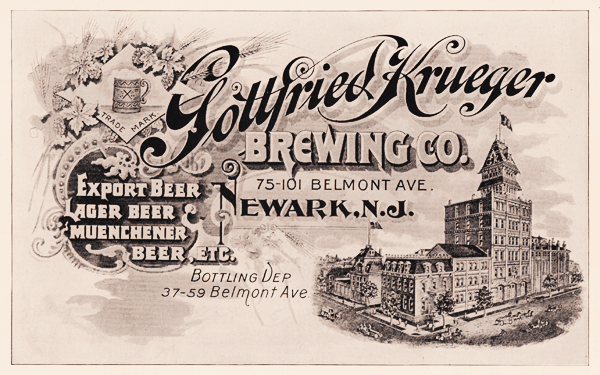

On the evening of September 25, 1883, the hottest party in Newark was at Gottfried Krueger's brewery on Belmont Avenue. The crowd of 5,000 included congressmen, senators, assemblymen, judges, mayors and police officials. Any one lacking directions needed only to look for the novel glow of electric lights and the 140-foot tall Gothic malt tower, topped by an American flag and the initials "GK". Why the celebration? It was the grand opening of Gottfried Krueger's spectacular new brewery. While music and good cheer filled the courtyard outside, guests inside the brewery marveled at the shiny copper brew kettles, gigantic oak fermenting casks and the endless array of pipes, pumps, hoses and vats. Liberal samples of the brewery's product flowed as proud employees educated their guests on the finer points of beer-making.

The new plant was the latest milestone in a family brewing tradition that would span more than a century in Newark. It began in 1853, when a teenage Gottfried Krueger arrived in America fresh from his birthplace on the banks of Germany's famous Rhine River. Newark, like most major cities, boasted dozens of breweries by mid-century. One such venture was the firm of Adams & Laible, who established a brewery on Belmont Avenue at West Kinney Street in 1851. It was here that young Gottfried would learn his craft, starting as a brewmaster's apprentice to Laible, his uncle.

Just at this time, the brewing of beer on this side of the Atlantic was on the verge of a radical transformation. While heavy British-style brews like ale, porter and stout had been the norm in America for generations, an exploding population of European immigrants spurred a demand for the lighter, less alcoholic German-style lager beer. Within a short time, German immigrant brewers had perfected a uniquely American version of lager beer—a light, effervescent, golden brew that would soon capture the nation's palate and build great fortunes for its makers.

After climbing to the position of brewmaster working for his uncle, Krueger purchased the brewery on Belmont Avenue in 1865 in partnership with Gottlieb Hill. As the popularity of lager beer soared, so did the brewery's sales. When the two partners took over the business, it was producing no more than 4,000 barrels (31 gallons per barrel) of lager beer annually. By 1875, sales had blossomed to 25,000 barrels per year, requiring almost constant enlargement of the brewing facilities. During that same year, Hill retired and Krueger became the brewery's sole owner.

The ever-burgeoning condition of their industry offered German-American brewers inroads to positions of leadership within the community. Of this, Gottfried Krueger took full advantage. He was first elected Freeholder, and then, in 1876 and 1879, served as a New Jersey Assemblyman. In 1891, he was appointed Judge of the Court of Errors and Appeals, a position he held for 11 years. Known forever afterward as "Judge Krueger" by his friends and business associates, the brewer served on the boards of a variety of corporations and was president of the New Jersey Brewers Association.

As the 20th century dawned, the first generation of German-American brewers could reflect with great pride on what they had accomplished over the previous fifty years. The consumption of beer in America had exploded from a paltry 750,000 barrels in 1850 to over 39,000,000 barrels in 1900. Small, wood-frame breweries had long ago been replaced by palatial Victorian-style edifices that stood as monuments to the grand success of the German-American brewers. Lager beer had, indeed, become the national beverage. It would now fall upon the next generation to carry the industry through its next half century.

At the Krueger brewery, sons John F. and Gottfried C. Krueger had each joined their father in the family business by 1903. It was this generation that would face the brewing industry's first great challenge. While beer was busy embedding itself into American culture, the ever-present temperance movement had been making strides of it's own. Groups like the Women's Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League had grown to include tens of thousands of members nationwide, and their influence was felt by brewers everywhere.

The outbreak of war in Europe in 1914 only made matters worse, as a rampant anti-German sentiment swept the nation. In Pennsylvania and Texas, well-publicized investigations of the brewers in those states painted the entire industry as unpatriotic and pro-German. Lubricated by the feverish wartime climate, the push for National Prohibition glided through Congress and the state legislatures with astonishing ease. It was the brewers' worst nightmare come true.

On January 16, 1920, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution took affect and the manufacture of beer became a federal crime. Many brewers turned to soft drinks, dairy products and low-alcohol near beer. Among other offerings, the Krueger brewery produced a near beer called Krueger's Old Essex Brew, which mimicked the taste of real beer, but contained less than the 1/2 of 1 percent of alcohol permitted by law.

Largely through President Theodore Roosevelt's prodding of Congress, beer again became legal at 12:01 am on April 7, 1933—an event that revelers dubbed "New Beer's Eve." Around the country, beer drinkers celebrated as brewery whistles blared and old-fashioned beer wagons paraded through city streets. As one of only a few New Jersey breweries still making near beer, the Krueger brewery was in a prime position to supply "the real stuff" the moment it became legal. In the first eighteen hours, the Krueger brewery sent out 35,000 barrels of beer and still had orders it could not fill. Sadly, Gottfried Krueger did not survive to see the banner day. He had died in 1926 at age 89.

As the initial hoopla over beer's triumphant return began to fade, brewers were left facing a harsh new reality. Congress had re-legalized beer mainly to provide new revenue streams, and so a hefty $5.00 per barrel tax was imposed. State taxes, which averaged $1.17 per barrel during the 1930s, were another new menace. Then, too, the nation was in the midst of a Depression. While some predicted that beer sales would quickly reach their pre-prohibition levels, that would not happen for many years. Over-capacity and slim profit margins created a high mortality rate within the industry. Between 1935 and 1945, the number of America breweries fell from 766 to 468.

Nevertheless, optimism ran high at the Krueger brewery. Despite the tough conditions, a good beer, a strong financial position and an innovative marketing strategy could bring success. Under president William Krueger, the company scored an important victory when it became the first brewer to sell beer in cans in 1934. Before prohibition, the vast majority of beer was served over bar tops. But with the advent of iceboxes in the household, the consumption of beer inside the home grew enormously, and the beer can was a perfect fit. Cans chilled the beer faster, took up far less space than bottles, required no return/deposit, and were significantly lighter and easier to transport.

But, in the end, massive sales volume was the only means of survival. By the mid-1950s, nationally-shipping brewers like Anheuser-Busch, Pabst, Schlitz and others had grabbed significant shares of the beer market in virtually every city in the nation. Their economies of scale, low production costs, streamlined distribution systems, and astronomical advertising budgets eroded the fragile markets of small, regional brewers.

They began to drop like flies. In 1961, the Krueger brewery drained its tanks of their last trickles of beer and closed its doors for good. Relentless competition added the Krueger brewery to its long list of victims. The venerable Krueger label was sold to the Narragansett Brewing Company, which brewed its version of the brand in Rhode Island and shipped it back to Newark to tap any lingering demand for the century-old brew. But, of course, it was never the same. Krueger Beer—true Krueger Beer—was gone forever.

|