[an error occurred while processing this directive]

Antique Beer Photos:

Dozens of prints available in a variety of sizes up to 40x50. |  |

|

|

The following article (complete with 1969 vernacular) appeared in the December 1969 edition of Brewers Digest.

For A Brighter Future...

BLACK PRIDE.

Black Pride, Inc., a for-profit corporation based in Chicago, Ill., has no connections with United Black Enterprises of Milwaukee, Wis., a group which in July of this year attempted to acquire the Blatz brewing operations, which a federal court ruled had to be sold by the Pabst Brewing Co. Also, while Black Pride, Inc., anticipates the support of blacks of a vast number of affiliations, Black Pride, Inc., has no connection with any other organization.

ON MONDAY, November 24, [1969] a new beer, labeled ''Black Pride," received its initial commercial distribution on the south side of Chicago, Ill. -- an area which includes a large portion of the city's approximately 1,200,000 blacks. It is more than a new beer label that has entered the market; it is a concept that is being introduced as well and, in

a sense, the particular product -- beer -- is secondary to the concept.

Since the concept involves economic, social and political implications, any one of these aspects could be used as the starting point for describing the concept. Because the immediate challenge for Black Pride, Inc., is to survive and to grow economically, the concept might be most simply identified as a marketing concept born of the black people's need to achieve economic stature in order to secure the political power that will assure social justice and respect for themselves.

Black Pride, Inc., was born out of the dying embers of black hope that the man (the whites) would magnanimously provide full economic opportunity for the blacks -- embers that the founders of Black Pride, Inc., are well aware can all too easily be fanned into a vicious conflagration when despair becomes desperation or when the justification for despair gives rise to individual irresponsibility.

Self-Reliance

Without forsaking the need of blacks to continue to pursue the right to equal opportunities through legal channels, the founders of Black Pride, Inc., recognize that a major roadblock to black progress has been the blacks' willingness to rely on white magnanimity. Too often the blacks' patience has been mistaken for shiftlessness, and as often, the Black Pride, Inc., founders acknowledge, many blacks have subserviently lived up to the mistake.

But it is not enough, they say, for the black simply to give up this psychology of dependence on white magnanimity, for where a self-defeating mood of despair does not supplant it, an equally self-defeating concept of presumptive "black power" will be likely to prove most attractive. Rather, what is needed on the part of the black is self-respect, a proper pride in himself. This is difficult to achieve and impossible to sustain unless, to speak in reverse chronological order, blacks have tangible evidence of personal achievement (among which would be upward mobility within a corporate structure) and the opportunity for such upward mobility and achievement. Thus, Black Pride, Inc., in the best tradition of the free enterprise system, seeks to provide a means of such achievement for its stockholders as well as for its employees and for those with whom it does business. At the same time, as an economic institution within the black community, Black Pride, Inc., hopes by the example of its success to reveal to blacks the ability of the free enterprise system to measure to their needs if they are willing to measure to its demands. Further, as an economic institution within the black community, and with its stockholders and employees being members of that community, more revenue in the form of profits, dividends, salaries and wages will be available for the assumption of greater local responsibility for community services and improvement. Finally, and here the marketing implications are obvious as well, the promotion of a Black Pride product intrinsically involves the promotion of the idea of blacks having pride in themselves and the necessity of personal effort and involvement if that pride is to be justified.

Founded in May

Black Pride, Inc., was registered as a Delaware corporation on May 28, 1969, and filed with the Secretary of the State of Illinois to do business in the state as of June 14, 1969. Its stockholders elect a board of nine directors which elects from within the membership of the board the officers of the company -- president, vice-president, treasurer and secretary. The executive committee of the corporation consists of the president, vice-president and treasurer.

The initial funding of the organization derives from 75 stockholders, each of whom invested $1,000 in the company. For further growth of the company additional stock is available for sale, and application for small business loans from the federal government can be made. Also, as the company develops, the board is authorized to devise franchising or distributorship arrangements for its products outside the Chicago area.

It is anticipated that Black Pride, Inc., ultimately would become a conglomerate, or highly diversified "umbrella" organization, with the addition of each new product or service -- at least at the outset -- being based on and related to a previous product or service. For example, the need to haul and deliver its beer could justify the acquisition of trucks which in turn could give rise to the development of a trucking division. Areas of further economic potential which have particular appeal for Black Pride, Inc., include printing, maintenance, surety, food co�-ops, home improvement and investment.  Headed by McClellan

Headed by McClellan

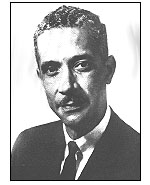

Black Pride, Inc., is the brain child of 47-year-old Edward J. McClellan who, in his capacity as the Urban Program director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Chicago, is well aware of the need of the blacks to upgrade them�selves economically. He is also thoroughly aware by virtue of his previous professional experience of the havoc that can result when people are frustrated by lack of the opportunities or conditions conducive of such upgrading. Born and reared on the south side of Chicago, he attended Chicago Public Schools and Illinois State University, Normal, Ill. In 1942 he entered military service and served with the 93rd Infantry Division in the South Pacific. In 1946 he became a counter-intelligent agent and remained with the Army Counter-Intelligence Corps until he resigned his commission in 1948. He then joined the Chicago Police Department, remaining on active duty with the department for 17 years. Presently he is on leave of absence from the department with the civil service rank of sergeant. Prior to taking a leave of absence, he was the commander of the Human Relations Section of the Chicago Police Department.

In December, 1966, Mr. McClellan was named executive secretary of the Southside Chicago Branch of the N.A.A.C.P., a position he still conti�nues to hold. Since he assumed this responsibility, the Southside Chicago Branch has grown from the ninth largest branch of the N.A.A.C.P. in the country to the largest, and now boasts a membership of 18,000. (In all of Chicago, the N.A.A.C.P. claims a membership of over 24,000.)

Mr. McClellan serves as a special consultant to the Community Relations Service of the U.S. Department of Justice and is a member of the Advisory Board to the Illinois Law Enforcement Commission.

Earl C. Vivian, aged 42, is vice-president of Black Pride, Inc. A native of Chicago, he attended the city's public schools and the School of Pharmacy of the University of Illinois. Following his discharge from the regular army in June, 1948, he joined the Illinois National Guard and is currently assigned to full time duty as personnel officer in the 33rd Military Police Battalion and occupies the position of staff administrative specialist and assistant adjutant. While in the regular army, Mr. Vivian served on the congressional board which submitted for consideration the system of the Enlisted Military Occupational Specialty now used by the U.S. Army.

Secretary and Treasurer

Serving as treasurer and secretary, respectively, of Black Pride, Inc., are E. Winston Williams and Elliot Mathews. Mr. Williams, now in his mid-fifties, is originally from Moss Point, Miss., but has resided in Chicago for the past 43 years. The third vice-president of the Southside Chicago Branch of the N.A.A.C.P. and a veteran of World War II, Mr. Williams is business representative for the Chicago Dining Room Employees Union, Local No.25, and is treasurer and manager of the Chicago Dining Room Employees Credit Union.

Mr. Mathews, 37 years of age, was born and raised in Chicago and attended the Chicago Public Schools as well as City College. He is presently on leave from the Chicago Police Department with which he had been associated for 11 years, the last five in the Community Services Division of the department.

The location of the company's headquarters and of the warehouse of the

Beer Division is at 1215 East 73rd St. on Chicago's south side.

Now a Distributorship

While Black Pride, Inc., has as its ultimate ambition to own and staff a brewery of its own, at the present time the company is licensed to operate as a beer distributorship for its own brand of beer, "Black Pride," and for such other brands as might prove advantageous. Black Pride, Inc., has entered into contract with the West Bend Lithia Co., West Bend, Wis., for West Bend Lithia to brew and package 20,000 barrels of beer annually under the "Black Pride" label. The contract also gives Black Pride, Inc., the distributorship for West Bend's own brands -- "Old Timer's Lager" and "Lithia Light" -- in the city of Chicago. These include a full range of packages, starting with the seven-ounce bottle, as well as draught beer. Finally, as the progress of Black Pride, Inc., warrants, West Bend agrees to provide blacks of Black Pride. Inc.'s designation with "a full cycle of brewing experience after the designate has completed satisfactory scholastic training in subjects basic to the art of brewing."

Brewed by West Bend

The West Bend Lithia Co., a 120-year-old brewery which for the past 80 years has been family-owned, is presently headed by Charles W. Walter, Jr. Located about 30 miles north of Milwaukee, Wis. (or about 120 miles north of Chicago), the company's plant has an annual capacity at present of about 75,000 barrels. The company is a member of the Wisconsin Brewers Association and the United States Brewers Association.

Thomas Heipp is the master brewer for West Bend Lithia. A graduate in 1934 of the Wahl-Henius Institute, a former brewmaster school in Chicago, he has been with West Bend Lithia since 1934. A long time member of the Master Brewers Association of America, Mr. Heipp has served as secretary of District Milwaukee, M.B.A.A.

Traditional brewing materials will be used and traditional procedures followed in the production of "Black Pride" lager beer, the founders of Black Pride, Inc., being convinced that blacks have no unique product characteristic preferences beyond that of high quality. To insure consistency in such product quality, Black Pride, Inc., will contract with an independent brewing laboratory for routine product evaluation.

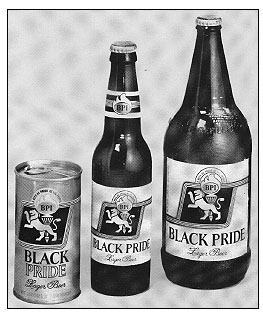

Attractive Packaging

The simple but attractively designed cases, cartons, cans and labels for "Black Pride" beer are dominated by black and gold color and carry the slogan, "A beer as proud as its people." Included, too, is the Black Pride, Inc., trademark: the letters "BPI" within the flame of a torch -- indicative of the "look to a brighter future" for all blacks that the Black Pride concept represents -- and a lion, a reminder of the African heritage the blacks have in common.

Initially, only packaged "Black Pride" is being distributed and in only six-packs of 12-ounce cans, loose packs of 24 12-ounce cans, cases of 24 12-ounce export returnable bottles and individual 32-ounce bottles.

The company at the present time has two International city delivery trucks and its warehouse has a capacity of about 20,000 cases.

Premium Prices

Pricing of "Black Pride" will be maintained at the premium beer level, and while the company is budgeted for advertising on a per case basis, initial advertising expenditures will be kept to an absolute minimum. Retail sales effort is being concentrated initially on the high volume carry-out outlets -- supermarket chains, package stores and chain drug operations -- with quick, concentrated follow up scheduled for on-premise outlets.

Cooperating with Black Pride, Inc., in the development of its promotional efforts is a class in marketing communications conducted by Dr. Harry Davis at the Graduate School of Business of the University of Chicago on the city's south side.

Franchises Offered

Black Pride, Inc., which has received numerous inquiries regarding franchises or distributorships from various parts of the country, expects to have at least five such distributors operative by mid-1970. While the franchise fee involved will be negotiated in terms of market potential, a minimum fee has been set of $5,000 annually plus $.05 per case. All franchises are subject to annual renewal, and Black Pride Inc., reserves to itself the right to designate product producers and suppliers, display and marketing techniques, employee training, administrative procedures, etc.

Why was beer chosen as the first product with which Black Pride, Inc., has become involved? The answer is simple, according to B.P.I. President McClellan. Surveys available to him revealed that expenditures for alcoholic beverages in the black area are high -- higher per capita than in predominantly white areas -- and that millions of dollars are spent annually for beer. Those same surveys evidenced that over 70 per cent of the market was held by three large breweries in the country with premium prices predominating. A ready market exists with a pricing structure that is conducive of a reasonable return on investment. At the same time, beer is sold to the retailer in Illinois on a cash basis, thus enabling B.P.I. to generate the greatest productivity from its capital resources. Adding to this is the relatively close shipping point of its product supplier, which results in less of a tie up of funds in product inventory.

No "Big Names"

Mr. McClellan, whose greying hair belies his youthful enthusiasm for the potential benefit to the blacks inherent in the success of B.P.I., emphasizes

that the company is not "star studded" and involves no "big names" either as investors or as advertising and customer contact personalities.

"Black Pride, Inc., is in every respect a bootstrap, grass roots endeavor," he says. "Our investors are 'plain folk' -- marginal income people who are pulling together without waiting for the man's help. Far, far too often the white sees the black as either a criminal or as someone on welfare. Ignored in the white's impression is the vast majority of the blacks who endeavor to live responsibly -- people who contribute much to the economy of the nation, but who have had too little opportunity to grow in position and affluence."

Primarily, the black is related to the economy as only a consumer, a customer, or as a salaried man or wage earner, Mr. McClellan points out. "Black Pride, Inc., stems from the need of black people to be able to exercise some control over the economics of the communities in which they live and thus to be able to shoulder a greater amount of responsibility for what those communities are. That economic control can only be achieved by blacks entering into the mainstream of the American economy as entrepreneurs, producers and purveyors.

Exodus of Dollars

"The exodus of dollars to the white suburbs which are earned in the black communities," Mr. McClellan adds, "does nothing to encourage the building of structures -- physical and social -- that are necessary to the maintenance of an orderly, stable and progressive black community."

Government action to encourage black enterprise, he says, has been unsuccessful for the most part because of bureaucratic waste and because "no one bothers to ask what the black himself wants." Mr. McClellan emphasizes that if the black truly wants to achieve full self-reliance or independence, he has to start by being self-reliant, by making the most of what he already has available to him.

Mr. McClellan does not condemn the white entrepreneur who does business in the black communities. "What we're saying is simply that we want to exercise the same right to do business within our own communities and to enable our communities to benefit from the profits and occupational opportunities deriving from such business. To the white who has reservations about our competitiveness, 1 would suggest only this: first, we are endeavoring to operate within the best traditions of the free enterprise system, and, second, the denial of the opportunity for, or the failure of, such boot�strap effort is an open invitation for blacks to remain on public dole or for the extremists to be successful in encouraging violence among the disillusioned."

Question of Separatism

Does this display of black independence encourage separatism by the whites from the blacks? "Hell," laughs Mr. McClellan, "few blacks have felt that close to the whites that the 'encouragement of separatism' has any meaning. We are separate, and the only way we can bring ourselves into a mutually respectful relationship with the whites is by securing the economic and political power that other minority groups in the U.S. long ago secured for themselves. And, I might add, most of those minority groups had a lot more going for them at the outset than had the blacks -- they didn't arrive here in bondage and they had the psychological and economic advantage of ties deriving from old world institutions -- the church, fraternal groups and the like."

To the suggestion that in the introduction of Black Pride products and services a very small minority of the blacks are using a moral issue -- the plight of the blacks -- for private gain, Mr. McClellan replies "Even if that were the case, at least the private gain would be remaining within the black community. Obviously, far more is involved than that. We're not using a moral issue; we're raising the moral issue but in such a way as to make the black responsive with regard to his responsibilities toward it. We want our success to serve as an example to others of what we blacks can do, must do, for ourselves. Without this, a great majority of our youth has little more to look forward to than degradation and, ultimately, degeneration."

"Personal involvement," he says, is vital to a satisfying life, but without the opportunity for responsibility, for achievement and for the attendant rewards, there is little stimulation to being involved."

Certainly "involvement" is a key word in the operation of Black Pride, Inc. In purchasing stock in the company, many of the people who had no previous knowledge of corporate financial matters have been subjected to training in this respect through the stockholders' meetings and other informal meetings with the company s officers. To keep costs to a minimum, male stockholders are scheduled to assist in unloading incoming beer shipments, and once the warehouse is taken over completely by B.P.I. they will perform the complete clean up job. With this done, some of the female stockholders will paint the walls.

While calls on the major off-premise outlets are the responsibility of B.P.I.'s staff, each of the company's stockholders is committed to spending the hour between seven and eight on Saturday evenings making calls on on-premise outlets in their neighborhoods in an effort to secure distribution.

This is not to suggest, says Mr. McClellan, that any pressure tactics, threats of boycotts, etc., are used on retailers. "A 'no thanks' or 'I'm not interested' would be graciously accepted, but that hasn't yet been the response our people have received."

"Further," he says, "all taste tests that we've conducted among consumers and retailers have been highly favorable for our product, with most tasters identifying the unlabeled product as one among the top sellers in the market."

A Major Problem

Mr. McClellan points out that one of the major problems for B.P.I. is to convince the black community that there is no white money behind Black Pride, Inc., and that "Black Pride" beer is a brand owned and financed exclusively by blacks.

"The quality of 'Black Pride' beer warrants, in our estimation, the premium price that we charge for it," says Mr. McClellan, "and the premium price carries with it the conviction of product quality. But for promotion of the product we will need to rely heavily on word-of-mouth. In this respect, it is perhaps fortunate that our lack of great capital resources has not enabled us to be tempted to become involved in extensive advertising. The brewing companies through their own brand advertising promote beer generically and, of course, we'll benefit from that. But slick, professionally produced advertising appearing extensively on TV and billboards on behalf of "Black Pride" beer at this time would only reinforce any suspicion that we might be fronting for white money. Actually, the only two advertising pieces that we have used are silk screen bumper stickers which say simply 'Black Pride beer is here,' and a one-page mimeographed sheet signed by myself which tells 'The Black Pride Beer Story': from a beer of distinction to the concept which has distinct implications for the black community."

What has been the reaction of the community leaders on Chicago's south side to the Black Pride concept and to "Black Pride" beer? Mr. McClellan states that to date it has been entirely favorable. "Certainly no one better understands the problems of the blacks than do these people and they are well aware of the importance of local economic viability to the ultimate solution of those problems. Even some clergymen while not inclined to promote beer from the pulpit -- ours or anyone elses -- have evidenced positive interest in our efforts."

What of Competition?

And what of competition? "We're not kidding ourselves about the strength of the existing brands within the market," says Mr. McClellan. "We surely are aware that we can never do 100 percent of the beer business, but we do hope to do a fair share of it. One of our problems at this point, as it is for any company introducing a new product or a new brand, is out to over-generate enthusiasm so that interest in the product is dissipated when the product finally is available in a given area. As far as competition from black owned companies within the black community is concerned, nothing would please us more than seeing this develop for it would be the best kind of proof that our concept had taken hold. And by competition in the beer business, I mean something more than a few small and relatively unprofitable distributorships."

"Actually," Mr. McClellan goes on to say, "we are trying to be thoroughly realistic in our projections and in our operations. Sure we have high hopes and high ideals, but we also know that what translates hopes and ideals into a realistic circumstance is personal dedication and sweat and more sweat. Of course, the possibility of success implies the possibility of failure. We accept that possibility, but if we fail, it will at least be on our own terms and it won't be because we haven't tried to succeed. There's dignity in that, too.

If enthusiasm and dedication, touched by wisdom and wrapped in humility and friendliness, are a measure of proper pride, then as personified in Mr. McClellan, Black Pride, Inc., has the necessary ingredients for success.

[Webmaster's Note: According to Who's Who In Brew (privately published, 1978), Black Pride Beer was brewed until 1972, the same year that the West Bend Lithia Brewing Company closed.]

|