[an error occurred while processing this directive]

Antique Beer Photos:

Dozens of prints available in a variety of sizes up to 40x50. |  |

|

|

The Rise of the Beer Barons

by Carl Miller

Reprinted from All About Beer Magazine.

Captain Frederick Pabst strode proudly through the various departments of his Milwaukee brewery. Flanked by a guest, New York Governor Roswell P. Flowers, the Captain was always at his best when showing off his world-class brewery to some visiting dignitary. The Governor could not help but to be impressed by the sheer enormity of the Pabst operation -- the gargantuan copper brew kettles stretching two stories in height, the towering oak fermenters capped by pillows of white foam, the endless rows of rotund casks filled with aging beer, and the army of busy German workers tending to their various duties. The Captain was particularly proud of the brewery's work force. Many years spent as a steamship captain on Lake Michigan taught him the value of employing only the strongest and fittest men. Wishing to boast this to his guest, Pabst could not resist an impromptu demonstration.

"You see that fire bucket hanging on the wall?" asked Captain Pabst. "Any of my men can fill that pail with beer and drink it down as you would a glassful." Turning to a nearby employee to prove it, the Captain said in a raised voice, "Isn't that so, Pete?"

"Ja, Herr Captain," replied the worker, "but would you excuse me just one minute?"

The worker retreated to an adjacent room. Upon his return, he filled the fire bucket with beer, hoisted it to his mouth, and proceeded to drain it in one long pull. Amazed and impressed by the feat, the Governor and the Captain congratulated the beaming employee and proceeded with their tour of the brewery. A curious Captain Pabst later asked the worker why it had been necessary to leave the room before emptying the bucket. The employee replied, somewhat embarrassed, "Vell, Captain, I didn't know for sure could I do it. So I just went to try it first."

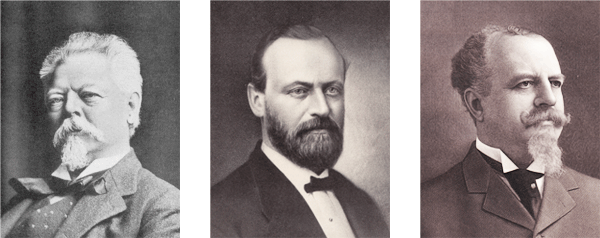

Frederick Pabst, Joseph Schlitz and Adolphus Busch.

Models of Success

Indeed, life inside a 19th-century American brewery required, at minimum, a hearty disposition. The work was arduous and the hours long. But, for many German immigrants, working in a brewery was a coveted privilege. Particularly within German-American enclaves, the local brewery was often the nucleus of its neighborhood. Lager beer, after all, was at the heart of daily life for many German immigrants, and its makers took great pride in producing the best they could. Brewmasters commanded unmatched respect, enjoying the status of virtual nobility. And the brewery owners -- with their great wealth and position in the community -- embodied the very success of the German people in America.

Their prosperity was made possible by the more than four million Germans who departed their homeland for new life in America throughout the last half of the 19th century. Not surprisingly, the Germans' timeless affinity for beer was one of the few precious traditions not left behind in the great exodus. As droves of immigrants landed on American shores, beermaking entered a new era. Names like Busch, Pabst, Schlitz, Ruppert, Ehret and many others became synonymous with beer, and were soon destined to rank among the greatest names in all of American industry. Without question, the age of the "Beer Barons" had arrived.

The utter transformation of the American beer scene by the Germans, although astonishingly rapid, was not immediate. Most of the men who would come to rule the industry -- and amass great wealth doing it -- came from typically humble beginnings. One observer painted a rather unflattering picture of the early immigrant brewer:

"The German artisan who founded the American beer industry was a kind of special cook with a trade recipe he had learned in Germany. He began by boiling beer in small quantities in family kettles or wash-boilers, and often, with his wife, retailed it to a German trade in a small saloon. The man and wife were typical Germans of the working class -- industrious, frugal, honest, and rather unsophisticated. The old-time brewmaster worked in necessarily uncleanly underground cellars, full of the drip of great ice-houses overhead, and of quantities of carbonic acid gas, sufficient to smother small animals, below; with floors saturated with the organic matter of former brews, and slippery with the molds that grow under such conditions. In this place he tramped -- a heavy figure in a slouch hat, course workman's clothes, and high leather boots. But for his special cook's knowledge of brewing, he dominated the brewing industry."

Empires On The Rise

The earliest of the German brewers in America brewed, by necessity, only top-fermented English style brews -- mainly ales and stouts. Not until the 1840s and 50s, with the arrival of bottom-fermenting lager beer yeast from Europe, could German brewers produce the Bavarian-style lagers and golden pilsners that would ultimately become their trademark in America. Reflecting on the long-anticipated arrival of lager beer in his town, one old immigrant commented, "To have lager beer from the tap in the land of hard liquor, what German friendly to drinking could not have felt the pull of home?"

And feel it they did. By the mid-1870s, the number of breweries operating in America had blossomed to an astounding 4,000. Over the next twenty-five years, the nation's beer production soared from about 10 million barrels (31 gallons per barrel) to nearly 40 million barrels per year. Brewery owners who once spent 18-hour days slaving over malt kilns and brew kettles now began to reap the rewards of their labor. As the never-ending stream of European immigration continued to flow, beermaking dynasties were being forged in virtually every city in the nation. Almost exclusively, Germans were at the helm.

In St. Louis, Adolphus Busch was busy transforming his father-in-law's (Eberhard Anheuser's) once-failing brewery into a grand empire. Adolphus, perhaps more than any other brewer, became known for his flamboyant, almost audacious persona. Tirelessly promoting his Budweiser Beer, he toured the country in a luxurious railroad car immodestly named "The Adolphus." In place of the standard calling card, the young entrepreneur presented friends and business associates with his trademark gold-plated pocket knife featuring a peephole in which could be viewed a likeness of Adolphus himself. His workers bowed in deference as he passed. "See, just like der king!" he liked to say.

In New York City, brewery owner George Ehret enjoyed a similar majesty. Affectionately nicknamed "the crazy Dutchman" despite his German birth, Ehret was the quintessential beer baron. Within a mere dozen years after its founding in 1866, Ehret's Hell Gate Brewery (named for the neighborhood in which it was located) was producing more beer than any other brewery in the country. Investing much of his profit in real estate, the crazy Dutchman ultimately ranked near the infamous Astors in the value of his property holdings in the city.

However, it was one of Ehret's competitors, brewer Jacob Ruppert, who won the hearts of New Yorkers. Colonel Ruppert, as he was known, bought the New York Yankees in 1915 and transformed the struggling baseball team into the American League powerhouse of their day. Using his vast beer profits, the Colonel built Yankee Stadium and bought talent like Babe Ruth and Waite Hoyt. During the twenty-four years the Colonel owned the team, the Yankees won seven World Championships and boasted some of history's greatest players.

Milwaukee: The Brew City

Of course, there were no beer barons like those of Milwaukee -- the city virtually built on malt and hops. The unmatched quantities of beer consumed in the brew city during the 19th century gave rise to the popular term "Milwaukee goiter," used to refer to a rounded belly. A well-known joke of the day said that every kitchen sink in Milwaukee had three faucets -- one for hot water, one for cold water, and the biggest for beer.

Captain Frederick Pabst can perhaps claim the lion's share of credit for Milwaukee's status as a world-renown brewing center. In 1893, the Captain became the first brewer in America to sell more than one million barrels of beer in a single year. (Though the majority was packaged in wood kegs, the brewery used 300,000 yards of blue ribbon each year to tie around the bottle necks of its popular Pabst Select brand. The name, of course, was later changed to Pabst Blue Ribbon.) By the turn-of-the-century, Pabst beer was being enjoyed in virtually every major city in the country.

That being the case, Captain Pabst undoubtedly took exception to competitor Schlitz's long-time slogan, "The Beer That Made Milwaukee Famous." In fact, Pabst snidely countered with a slogan of his own: "Milwaukee beer is famous -- Pabst has made it so." Joseph Schlitz, however, may have gotten the final word in the rivalry. Before his tragic death during a shipwreck in the Atlantic in 1875, Schlitz had mandated in his will that his brewery never bear any name other than Schlitz. For more than one hundred years afterward, the two Milwaukee breweries battled for the top position among America's beermakers, both achieving great prosperity along the way.

The German Social Icon

No question: To the beer barons, beer meant wealth and success. However, to the countless German-American immigrants of the late-19th century, lager beer meant something far different. Lager beer was, perhaps more than anything else, a social icon. It represented family, friends, and German camaraderie. And nowhere was this more true than at the local beer garden. A weekend resort laid out amidst shady trees and sprawling lawns, the typical beer garden was manicured to be the perfect setting for that most important of 19th century pastimes: quaffing the amber fluid. And there was barely an American town in the mid- to late-1800s that did not boast one (or two, or three) of these beer drinking utopias.

After all, the beer garden provided something which most immigrant-Americans could not get anywhere else -- something the Germans called gemutlichkeit. Near and dear to the heart of the average Teuton, gemutlichkeit was a sort of cozy, warm state of being created only by the presence of good friends, close family, a relaxing environment, and, more often than not, plenty of beer.

But the typical beer garden offered far more than just beer and gemutlichkeit. There was music, dancing, sport and leisure. It was an occasion for the whole family, and one which usually lasted the entire day, from sunup to sundown. Indeed, for the mostly working class throngs who came, the beer garden was an oasis in an otherwise workaday life. As such, it played an important role in the lives of countless immigrants.

Milwaukee, of course, was the undisputed leader in the number (and extravagance) of beer gardens. Competition between the city's dozens of gardens was fierce, and all manner of entertainment was employed to lure a large beer-drinking crowd. Lueddemann's Garden, for example, once featured a "daring and beautiful" female performer who set fire to herself and plunged 40 feet into the river below, much to the delight of on-lookers.

However, those gardens which were owned by the beer barons themselves featured the most popular attractions. In 1879, the Schlitz brewery bought a local beer garden and turned it into a magnificent resort, appropriately renamed Schlitz Park. The large garden was a virtual entertainment mecca, featuring a concert pavilion, a dance hall, a bowling alley, refreshment parlors, and live performers such as tightrope walkers and other circus-style entertainers. In the center of the park was a hill topped by a three-story pagoda-like structure which offered a panoramic view of the city. At night, the garden was dramatically illuminated by the 250 gas globes which lined the terrace of the central hill. The park was a popular spot for political gatherings. Among those who made speeches at Schlitz Park over the years were Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt and William Jennings Bryan.

Not to be outdone by his hometown rival, Captain Pabst operated Pabst Park in Milwaukee (among other beer gardens). The eight-acre resort boasted a 15,000-foot-long roller coaster, a "Katzenjammer palace" fun house, and an oddity touted as "the smallest real railroad in the world." Wild west shows were held on a regular basis, and live orchestras performed seven days a week all through summer. Of course, whatever the attraction, a 5¢ schooner of cold Pabst Beer was never far from reach.

While both Schlitz and Pabst appealed to the more adventuresome and thrill-seeking of Milwaukee's German community, Frederick Miller's garden on the western outskirts of the city catered to a somewhat more reserved clientele. A visitor to Miller's Garden wrote in 1873: "The garden, situated on a lofty eminence, overlooking a wide stretch of green and rolling country...is a very pleasing place to while away the hours of a scorching afternoon. Seated at a rustic table beneath leafy bowers, men and women, staid and middle-aged, during pauses in their friendly conversation, sipped their amber lager. In the spacious pavilion, Clauder's band rendered sweet music."

Major Beer Properties

The Milwaukee beer barons did not, by any means, limit their beer drinking spots to the confines of Milwaukee. The Schlitz brewery, for instance, operated gardens and saloons in major cities throughout the country. In Chicago alone, Schlitz owned some sixty different properties around the turn of the century. Captain Pabst, too, was a large holder of saloons and restaurants outside Milwaukee. When the Captain decided to invade New York City, he did so in grand fashion, opening the Pabst Hotel in 1899 and the Pabst Harlem in 1900. Claiming to be the largest restaurant in America, the Pabst Harlem was capable of seating 1,400 patrons at once. It was said that the Captain hired famous New York stage actors to walk into the Harlem, order a beer, and say in a loud voice, "I am drinking to the health of Milwaukee's greatest beer brewer, Captain Fred Pabst."

The Barons' Undoing

Given that the beer barons of the late 19th and early 20th century sold their brew -- and, thus, built their fortunes -- almost exclusively through beer gardens and saloons, it is a little ironic that those very establishments ultimately contributed to their undoing. Historically speaking, the Prohibition movement in America targeted not the brewer, not the distiller, not even the drunkard, but rather the disreputable saloon -- those urban "grogshops" where, according to the prohibitionists, prostitution and gambling ran wild. Indeed, far and away the most important force in bringing about National Prohibition (1920-1933) was the Anti-Saloon League. While the League's central goal was most certainly the complete destruction of the alcoholic beverage industry in America, its strategists believed that the saloon was the Achilles Heal which could bring victory to their cause. And, much to the dismay of the beer barons, the theory proved supremely effective in the end.

Although Prohibition put an abrupt end to what has been called "the golden age" of beermaking in America, vestiges of that era are still everywhere around us. The brewing industry, after all, is steeped in tradition like few other industries in America. Unusually strong rights of inheritance have kept many American breweries under the same familial management for generations. Brewers like Anheuser-Busch, Miller, Coors, Pabst and others, while not all controlled by their founding families today, nevertheless carry a century-old legacy rooted in the Gilded Age prosperity of the German-American beer barons. So great was their influence on brewing in America that, more than a century later, their names live on in testament to their grand achievements.

Post Script:

THE MYSTERY OF AMERICAN LAGER

Everybody loves a mystery. Add beer to the story, and it gets even better. Its an enigma that has endured for more than 150 years, and one that goes to the very roots of beermaking in America. The question is simple: Who brewed America's first lager beer? The answer, however, has been a source of hot debate almost from the very beginning.

It comes as no surprise that the more nostalgic-minded of America's 19th century beer barons sought to document and record their achievements for posterity. And where better to begin the story than at the beginning? Thus, the question of who brewed the nation's first lager has always been an important one, particularly to the brewers themselves. That being the case, its a little ironic that so much uncertainty and speculation has surrounded the issue for so long.

Through it all, however, there has emerged one account of the event in question that has endured more than a century of efforts to dispute it. The common wisdom says that America's first lager beer was brewed in 1840 by one John Wagner in a "miserable shanty on the outskirts of Philadelphia." The milestone was not accompanied by any splash or fanfare, although the precious bottom-fermentation yeast was rare enough to become the target of a theft by Wagner's brother-in-law, for which he was sentenced to two years in the state penitentiary. Although substantiated by at least two of the day's prominent brewers (Frederick Lauer and Charles Wolf), the story of Wagner's inauguration of lager beer into America has always carried with it a certain cloud of suspicion.

For example, one dissenter by the name of Bacon, staunch in his assertion that lager beer had been present in America as far back as the early 1700s, published his argument in Leslie's Popular Monthly -- a sort of Saturday Evening Post of the 19th century. Bacon plead his case with the aid of several somewhat thinly-supported, yet nevertheless plausible, examples of early American brewing. A certain stone brewhouse on Nassau Street in New York City, for instance, was allegedly popular for 40 years for its annual tapping of lager beer each spring until it closed in 1750. Bacon concludes, "It came and went with the Spring, making no special sensation or record, and therefore the existence of that early American lager has been overlooked and forgotten." Another of Bacon's examples recited the legend of the "lager beer bell" of York, Pennsylvania. It was said that, in celebrating the arrival of the hamlet's first church bell in 1745, the townsfolk upturned the bell, filled it with lager beer from the local brewery, and -- one by one -- drank from the bell in ceremonious order.

Be that as it may, the major caveat in Bacon's whole argument was that true lager beer was merely that which "slept through the Winter and awoke ripe and bracing in the Spring." In other words, questions of fermentation -- top, bottom, or otherwise -- had no bearing on the subject in Bacon's view. So is it possible that this 150-year-old debate boils down to a simple matter of semantics concerning the definition of lager? Well, yes and no. Given that bottom-fermentation has been a cardinal component of lager by virtually every practical brewer since Bacon's time, his argument must necessarily be flawed.

However, there has been claim made on the part of various other brewers as having introduced bottom-fermentation lager into America before Wagner. The Adam Lemp brewery of St. Louis, for example, is said to have produced lager beer as early 1838, although no corroborative evidence has been unearthed to support the claim. Indeed, until the proverbial "smoking gun" finds its way out of some dusty archive, Wagner's title as the father of American lager beer will remain intact.

Copyright 1999 Carl Miller

|