|

The following article was researched and written by Carl Miller for the Portsmouth (Ohio) Daily Times.

Breweries Once Flourished in Portsmouth. Breweries Once Flourished in Portsmouth.

According to legend, a 12th century Flemish nobleman, King Gambrinus, brewed the world's first barrel of beer. In reality, some form of beer is known to have existed centuries earlier. Nevertheless, King

Gambrinus -- invariably portrayed with foaming goblet held high in mid-

toast -- has long been established as a symbol of the universal and eternal

regard for beer.

Indeed, the King's rule has been felt just about everywhere,

including Portsmouth, which has been home to more than one brewery

throughout its nearly 200-year history.

The first known commercial brewery in the city was established in

1843 in a small frame building on the west end of Second street near

Madison. Known simply as the "Portsmouth Brewery," the venture was

under the management of partners Schiele and Muhlhauser. However, by

1845, Schiele had passed away, leaving Thomas H. Muhlhauser alone in the

business.

It is likely that the brewery initially made only English-style brews

such as ale, porter, stout and the like. But, being that Muhlhauser was a

native German, he most probably added the German-originated lager beer

-- most common today -- to his production when that beverage began its

rapid rise in popularity during the 1850s.

After Muhlhauser's death in 1858, his widow operated the brewery

in partnership with Felix Geiger, who came to Portsmouth from Jackson,

Ohio for that purpose. But, by 1864, local resident Frank Kleffner, who

had since married the widow Muhlhauser, was advertising himself as the

brewery's proprietor.

The Portsmouth Brewery had gained some local competition by this

time. Undoubtedly a result of the increasing number of Germans in the

city, a handful of breweries were established in Portsmouth during the

years just prior to the Civil War. Frederick Lauffer opened a brewery

and malt house on Front street between Jefferson and Madison, just around

the corner from the Portsmouth Brewery. The "City Brewery" was

established by John Layher next to his saloon on Sixth street west of

Chillicothe. And William Schirrmann set up a brewery on Chillicothe

between Seventh and Eighth streets.

Hard Times

The Civil War years were a difficult period for Portsmouth's

breweries. The departure of about 4,000 of Scioto County's young men --

now soldiers in the Union Army -- would have an obvious impact on the

consumption of beer locally. In addition, a federal tax of $1 per barrel of

beer sold was imposed to help finance the war effort. Portsmouth brewers

eagerly awaited better times.

The conclusion of the war, however, brought little relief. The

federal tax was not lifted as anticipated. And the city's population growth,

which had enjoyed a steady rise for several decades, slowed substantially

during the 1870s, leaving the local beer market sluggish. By the middle of

that decade, only the original Portsmouth Brewery remained in operation.

Although having survived the difficult economic conditions, the

Portsmouth Brewery spent the next several years passing through a series

of changes in ownership.

In 1878, Frank Kleffner sold a half interest in the brewery to August

Maier, a European-trained brewer who had worked in Philadelphia and

Cincinnati before coming to Portsmouth. Conrad Gerlich, a local

businessman, joined the partnership in 1881. One year later, Kleffner and

Gerlich both sold their interests in the business to Henry Roettcher, a

recent arrival from Cincinnati. By 1884, Maier had sold his share to

Roettcher as well, and the latter was now the brewery's sole proprietor. Be

that as it may, Conrad Gerlich was back in control of the brewery by 1888.

The following year, the brewery changed hands yet again. But the

new owner, Julius Esselborn, was determined to make a success of the

business. The German immigrant paid $12,500 for the brewery and

reported that he would immediately invest another $10,000 in new

equipment and "improvements of all kinds."

Julius Esselborn had spent several years living in New York and,

later, in Cincinnati where he was a milliner and dealer in "fancy goods."

Exactly what prompted Esselborn and his family to travel to Portsmouth

and engage in the brewing business is not known.

Nevertheless, the Portsmouth Brewery flourished under Esselborn's

management. Various enlargements and improvements were made to the

works throughout the 1890s, including the construction of an entirely new

brewhouse. By 1904, the plant boasted an annual brewing capacity of

20,000 barrels of beer (32 gallons per barrel).

The brewery was merged with a local ice company in 1892 and

incorporated as "The Portsmouth Brewing and Ice Company." Due to the

requirement of cold temperatures throughout much of the brewing process,

many brewers chose to invest in their own ice-making facilities rather than

pay the high cost of obtaining ice from outside sources.

By the turn of the century, the ice plant was capable of producing

about 75 tons per day, only a small percentage of which was consumed by

the brewery. The remainder was sold to local households and businesses. In

an 1897 "industrial review" published by the Portsmouth Ladies Auxiliary,

it was noted that the company's ice "has always found ready sale because of

its purity." Interestingly, no mention was made of the fact that beer was

also produced by the company, lest the Ladies Auxiliary be accused of

contributing to the social evils of the day.

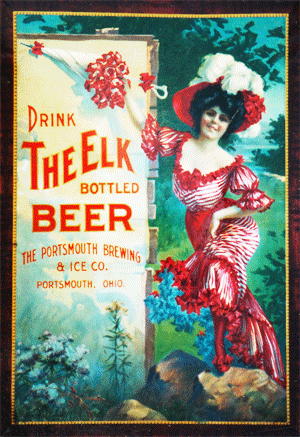

But, of course, beer was the company's cornerstone, and a variety of

different brands were marketed over the years. Among them were O.K.

Bohemian, Portsmouth Bock, Culmbacher, Excelsior Export, and The Elk

Beer. The latter brand, perhaps the most popular, was presumably named

in honor of the Portsmouth Elk's Lodge, an organization to which Julius

Esselborn was avidly devoted.

The Portsmouth brewery's primary trade was within Portsmouth

itself. However, a significant amount of "export" beer was shipped to

outlaying areas within a radius of about 50 miles. Quantities of beer were

undoubtedly sent up river to Huntington, West Virginia, possibly the

brewery's largest market outside of Portsmouth.

Although Cincinnati was one of the largest beer-consuming centers

in the Midwest, it was probably not a routine destination for Portsmouth

beer. The dozens of large breweries which thrived in the Queen City

before the turn of the century made it difficult for outsiders to gain a

strong foothold there. In fact, several large Cincinnati breweries

maintained distribution facilities in Portsmouth.

Waged largely in the saloon trade, competition from outside

companies was difficult for small regional brewers such as the Portsmouth

brewery. Aggressive and highly-capitalized brewing companies offered

Portsmouth saloonkeepers various incentives to sell only the sponsoring

brewery's brands. Favorable terms on fancy saloon fixtures, interest-free

loans, and payment of expensive license fees were among the more

common enticements. Forced into parallel tactics, the Portsmouth brewery

supplied bar fixtures to several of the city's saloonkeepers.

The Next Generation

On May 6, 1900, Julius Esselborn passed away at age 64. Although

his widow Pauline Esselborn was officially made president of the company,

it was son Paul Esselborn who seems to have actually taken over

management of the brewery.

The young Esselborn was no stranger to the brewing business, he

having spent many years working in the brewery with his father. He also

served as vice president of a local bank and trustee of the Portsmouth water

works. His involvement in both of these entities can clearly be tied to the

interests of the brewery.

The young Esselborn lead the brewery into what was perhaps the

most turbulent period in the history of the brewing industry. After the

turn of the century, the Anti-Saloon League and other prohibitionist groups

began making great strides for their cause all across the country. Ohio, in

particular, was a hotbed of prohibitionist activity.

In 1908, the Anti-Saloon League succeeded in affecting the

enactment of the Rose Law, which allowed every county within the state of

Ohio to vote its saloons out of existance. The vote in Scioto County came

down squarely on the side of the "drys," and all 55 saloons within the

county were ordered shut down.

Attacks on the saloon were not new to Portsmouth. The temperence

movement had been an ever-present annoyance to saloonkeepers and

brewers alike for decades. During the 1870s, bands of bible-toting

temperence advocates routinely made unannounced appearances at local

drinking establishments to demand an immediate cease of business. In 1874,

a group of Portsmouth crusaders reportedly convinced 17 of the city's

saloonkeepers to stop selling alcohol -- a heralded victory for the local

drys.

But the days of the old fashioned saloon raid were long gone, and

Ohio's Rose Law was a clear indication that legislation had become the tool

of the modern prohibitionists.

With the saloon now abolished throughout much of Ohio, it was

concluded that the Portsmouth Brewery had no alternative but to close its

doors. In what was called an "affecting scene" by a reporter for the Daily

Times, Paul Esselborn gathered his 40 employees inside the brewery to

deliver the bad news. Many were reduced to tears. The brewmaster of 26

years, Anton Schriek, reportedly "cried like a baby."

Somewhat ironically, just days after announcing the closing of his

brewery, Paul Esselborn was elected president of the Ohio Brewers'

Association, a position which he held for a number of years.

By 1911, it had become apparent that abolishing the saloon was not

an effective solution to the liquor problem, and the residents of Scioto

County voted to re-legalize saloons. The Portsmouth brewery was

promptly put back into operation by the Esselborns, and business resumed

as before.

Not long after its re-establishment, the brewery was stricken with

another temporary set back: the Great Flood of 1913. Although the

brewery was submerged in nine feet of water, Paul Esselborn reported

only minimal damage and the loss of a handful of kegs which floated away.

However, heavy damage was sustained by all of the city's saloons, many of

which were equipped with brewery-owned fixtures. The loss was said to

have represented a significant investment by the brewery. Once the flood

waters receded, Paul Esselborn wrote, "We're glad we are back on earth."

Prohibition Looms

Although saloons were again legal in Portsmouth, the relentless

pursuit of the prohibitionists soon spelled more trouble for Ohio's

breweries. In a 1918 referendum for statewide prohibition, Ohio was

officially voted completely dry. The following year, the National

Prohibition Amendment was ratified by the required 36th state (which

happened to be Ohio) and the entire nation entered what has been called

"The Noble Experiment."

Brewers nationwide were forced into new fields of business. Most

attempted to make use of their brewing equipment by producing dairy

products or soft drinks. The production of near beer (de-alcoholized beer)

was a popular alternative. The Portsmouth Brewing and Ice Company

briefly tried its hand at a near beer called "Flip," which contained less than

one-half of one percent of alcohol -- the legal limit.

However, the market quickly became saturated with similar

products, the result of countless breweries struggling for survival. And,

anyway, it was soon apparent that demand for a non-alcoholic beer simply

did not exist in any great abundance.

After the brewery closed in 1920, the bottling works was taken over

by the Portsmouth Whistle Bottling Company, and the ice-making plant

housed the new Portsmouth Ice and Fuel Company. Not wishing to continue

in beverage-related fields, the Esselborns left Portsmouth for Cincinnati,

where Paul Esselborn became involved in the machining business with

relatives.

The repeal of National Prohibition in 1933 meant the return of beer,

and it seemed likely that the Portsmouth brewery would be refurbished and

put back into operation. Indeed, a group of local investors organized "The

Germania Brewing Company" in 1938, intending to reopen the old

brewery. However, the venture did not fully materialize and Portsmouth's

brewery never again produced beer.

Paul Esselborn, incidentally, made his return to brewing in 1933

when he established the Clyffside Brewing Company in Cincinnati, where

he successfully brewed "Felsenbrau Beer" for a number of years.

The old Portsmouth brewhouse, which still stands on the west end of

Second street, has been used for a variety of purposes over the years.

Looking somewhat the worse for wear, the old structure serves as a quiet

reminder of an era long forgotten.

|